j

Lucas van Leyden's Painting "The Chess Players"

1508

A Detailed Analysis

courier game - kurrier - renaissance

- medieval - 8 by 12 - chess players - chess match - kurierschachspiel

- chess variants - ancient chess

|

Lucas

van Leyden was a master painter and leading engraver of the

16th century. If you find the perspective of his painting a

little askew, please cut the master a little slack. There is so much to see in this painting – the drama of the characters consulting and kibitzing, the detail of dress and expression, the implied time period and social milieu. What we are interested in here is the drama of the game in play on the great 8 by 12 courier chess board. Thanks

to the generous expository nature of van Leyden’s rendering,

and a little bit of historic insight, we can analyze the pieces

and position – and recreate the actual game in great detail. ANALYSIS OF THE GAME So,

what is this game presented in the painting? It is just a haphazard

arrangement of pieces or a carefully constructed real or possible

game? But then what piece is what? They are obviously conventional

“abstract” pieces of some tradition – but

this particular sort is long since forgotten! Can we possibly

make sense of this ancient array of figures? Let's look at what

we know, what we can observe ... and what can be revealed.

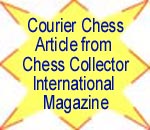

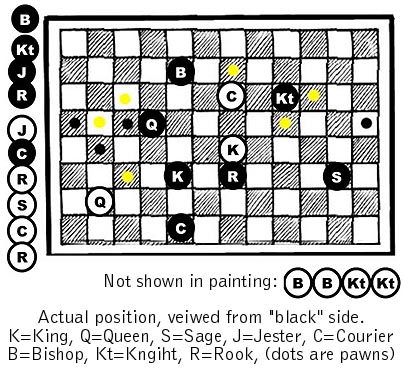

Let’s first look at the known information. Although no text survives to tell us simply what the strange figures on van Leyden’s board represent, we do have a record of how the game of courier chess was played. The initial array of pieces shown here is adapted from H.J.R. Murray (A History of Chess, 1913), who was informed by Gustav Selenus (Das Schach Oder Konig Spiel, 1616). Our view is from the side of “black”, to make easier reference to woman’s side in the painting. The pawns are just shown as spots (yellow on the “white side; black on the “black” side). Also from Selenus (1616), we get the moves of the pieces. Note that some pieces – bishop, queen and pawn – have their older, medieval, pre-16th century moves. Rook

– like our modern rook Furthermore,

we historic texts tell us that the game opened with four peculiar

moves on each side. Each player moved the two rook pawns, the

queen’s pawn, and the queen herself forward two spaces.

This opened the game more quickly, allowing the rooks and queens

to get into play quickly.

A, B, C and D are somewhat similar to each other. A looks like a big ball, but B looks a little squashed; C and D could be the same thing viewed “from the side”. This doesn’t look like any known piece, either ancient or modern – although it has some resemblance to the rooks in the painting “Three Sisters Playing Chess” (Sofonisba Anguissola, Italy, 1555). E has a split top, typical of medieval rooks or bishops. F is barely visible in the lower left corner of the board as seen in the painting, but seems to be of the same shape. Because of the medieval bishop’s very limited move – exactly two spaces diagonally – each bishop has only 12 spaces on the entire 96-square board that he can possibly move to. It happens that E stands on one of these possible squares, and could have reached it in three moves from the bishop's starting position. (Only one other piece – B, apparently a king – stands on another possible bishop-occupied square). G, H, I and J are very similar to each other, looking somewhat like the heads of modern bishops. They are taller than most pieces, perhaps indicating power or importance. Texts tell us that the courier was considered to be the most powerful piece (though modern players would disagree). K and L are the very symbol of kings in modern diagrams – but they may not be kings at all. That particular symbol didn’t come into fashion until the late 19th century. Still, one suspects that the crowns must indicate some sort of royalty. M and N (barely discernible behind the lady’s hand), also crowns, must also be some sort of royalty, but of less prestige or power. O and P appear to be the same figure at different angles. Could they be an abstracted horse’s head? That is one tradition that has survived many centuries, from medieval through modern times. Q and R are a peculiar sight to us today, but for several centuries this three-tiered Christmas tree was the established form of the king. Finally, S is similar to Q and R, but also similar to T which is painted with more care and detail. Jester? Queen? Courier? Bishop? It could be just about anything. Just looking at the pieces, with some knowledge of historic forms of chessmen gives us a few clues – but not enough to be very certain. What fills in the picture then, is the position of pieces on the board. Our working hypothesis is that this is a real game in progress, either recorded by the artist or deliberately created. If that isn’t the case, we’ll soon find that our position is ridiculous if not totally impossible.

White’s king pawn (adjacent to piece H) has not advanced. From this, we can surmise that the king's side is on the right and the queen's side is on the left – for if it were the queen’s pawn, it would have to be advanced two spaces in the opening. L is being threatened by a white pawn, but the woman playing black is not moving to defend it. This supports our assertion that K and L are not kings. They are, however, on the correct color squares to be queens (considering the medieval queen’s diagonal-only move) – and they happen to be working on the queen’s side of the board. M is out of play, while N is busy over on the “king’s side” (also the "sage's side) of the board. O, if it is a knight, could have easily reached its present position in 3 simple leaps (P is out of play). Q and R appear to be very active kings, with black moving a piece right up to the white king, possibly threatening it. S is apparently the same as the much more detailed figure T. No on-board evidence for this one … but with that ball, frilly collar and hat, it may well be a jester. Finally, we must consider that rooks, knights bishops and couriers come sets of two to each player, while kings, queens, jesters and sages come one to each side. So a piece that appears twice in one color must be one of the former pieces, while a piece that appears only once in each color is probably one of the latter.

So, taking all of this into account, here’s what we’ve come up with. Take a look at the diagram at right. With the pieces identified in this way, every piece is properly in play, in a legal and quite possible position. The woman playing black is just at the moment of giving check with a rook, which is defended by a courier. The white king is not yet trapped; he may move to either of the white squares adjacent to his own courier … and the pursuit will continue for a few moves yet, before black’s overwhelming forces finally trap the white king into a checkmate. AND SO … Having analyzed the position and derived the identities of the pieces, we have been able to recreate the entire set, as it would have been recognized at the dawn of the 16th century. Here is the starting line-up of the pieces. Quite a cast of characters! Charming, interestingly diverse – and powerfully inviting the 21st century player to step back in time and take part in one of Old Europe’s most enduring contests of wit!

|

The

Courier Chess Reproduction above:

The opening position of courier chess The

complete set of 48 pieces stand between ¾ inch

and 2 ¼ inches tall (1.8 ~ 6 cm), the same size of those

depicted in van Leyden’s painting. Since

the first production of in 2008, additional versions of the

chessmen and board have been created. See the link below for

currently available sets. Further

productions are being developed. Check our listings

for fine brass sets and hand made boards. CLICK

HERE FOR AVAILABLE

|

Quality

Print of Lucas van Leyden's Painting Original

size: The image is reproduced in the same size as

the original painting: |

|

THE

PUZZLE

THE

PUZZLE Now,

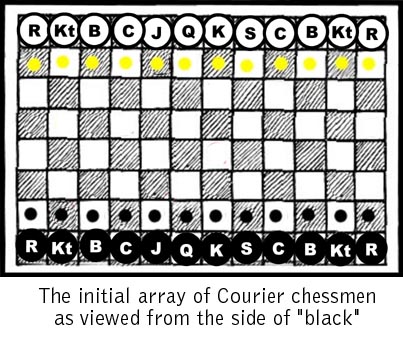

let’s look at these mysterious pieces, one by one. They

are shown here, isolated from the painting, and given letters,

A through T, for reference.

Now,

let’s look at these mysterious pieces, one by one. They

are shown here, isolated from the painting, and given letters,

A through T, for reference.  This

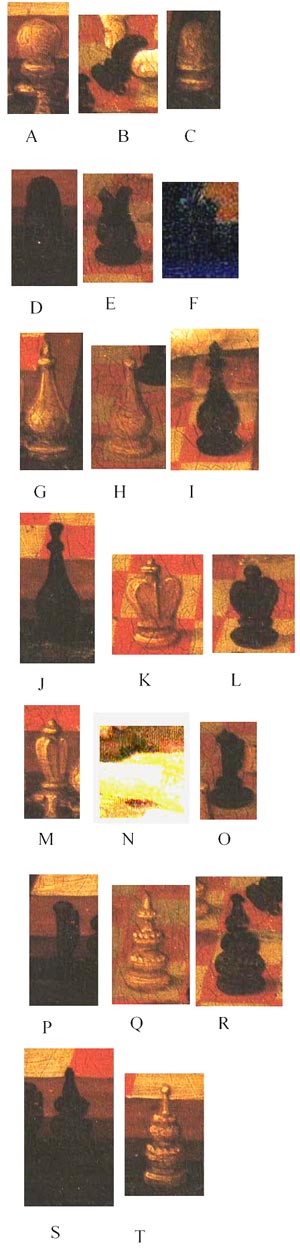

diagram shows the pieces laid out on and off the board, as they

are in the painting – using our letters, A through T as

reference. Let’s see what can be observed.

This

diagram shows the pieces laid out on and off the board, as they

are in the painting – using our letters, A through T as

reference. Let’s see what can be observed. SOLUTION

SOLUTION